In Living as a Bird (2019), associate professor of philosophy at the University of Liege Vinciane Despret suggests birds not only create defined territories, but are also constantly engaged in processes of deterritorialization, which can include displacements, social negotiations, and changes in the perception and use of space, in keeping with the notion of territorialization and deterritorialization proposed by Deleuze and Guattari, whereby territories are not static and fixed entities, but rather dynamic and fluid processes that constantly involve the creation and recreation of spaces and boundaries. This can occur through a variety of processes, such as migration, the invasion of new territories, political or cultural resistance, or the transformation of social relationships. Deterritorialization can lead to the destabilization of pre-existing boundaries and the creation of new forms of spatiality and belonging.

This approach challenges traditional conceptions of territories as static entities and highlights the fluidity and complexity of relationships between birds and their environment. Territorialisation is therefore not so much the act of making a space as something that one possesses but rather an expression of oneself.

The territory is not merely a static place, but one characterized by the expressiveness of rhythm, i.e. the ability to create and maintain a certain kind of interaction and communication within a specific space. According to Vinciane Despret, birds not only inhabit a physical space, but are also involved in a range of activities and behaviors that help define and maintain their territory. These include singing, nest-building, signaling the presence of predators, and negotiating social relationships with other individuals of the same and of different species. Birds sing to mark a territory, but the relationships between the bird, the song, the territory and the bird’s community are highly complex and individually variable.

For the author, the singing would be then an extension of the bird’s body in space.

In this sense Despret emphasizes that there would be a dynamic of reciprocity: appropriating a place consists in conforming it to oneself and in conforming to it.

It is with three birds of different species—the kingfisher, the green woodpecker and the hoopoe, representing the diversity of species that inhabit the Brembate Biodiversity Oasis—that artist Mercedes Azpilicueta stages the performance Que este mundo permanezca.

Right from the title, “May this world remain” suggests a reflection on the conservation of the natural environment, in which the concept of “world” may be interpreted in reference to biodiversity or even the harmonious coexistence between humans and the environment. Focusing on the histories and perspectives of birds, Azpilicueta invites us to embrace the plurality of voices and experiences in the animal world, challenging anthropocentric and privileged conceptions of humans as the gatekeepers of meaning and value.

Thus, by studying the behavior of birds and their interaction with the environment, the artist together with local performers have developed a nomadic, staged narrative.

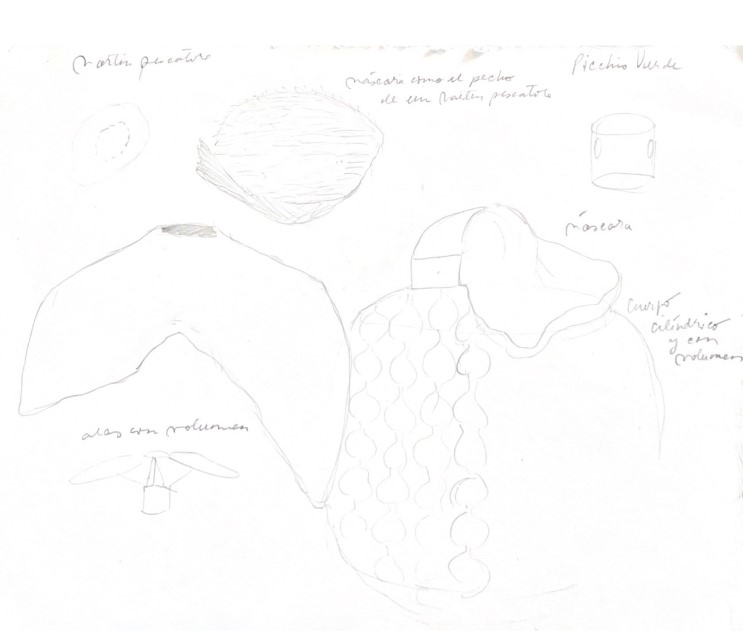

This collaborative approach in devising the performance reflects Azpilicueta’s artistic practice, which often involves various actors in the creative process. In fact, the artist has worked closely with Alberto Allegretti to create a series of carefully designed costumes and masks—made from discarded fabrics and other materials—that evoke the colors and peculiarities of these creatures’ plumage. The performers Nicola Forlani, Aurora Rota, accompanied by choreographer Antonella Fittipaldi, follow a script made up of gestures and movements, and tell of the animals’ ability to thrive and adapt to an environment which—by virtue of its particular composition and morphology—serves as a metaphor for transformation and which at the same time hosts a vibrant community.

Valentina Gervasoni

This introduction is followed by five questions posed to Mercedes Azpilicueta:

How would you describe the typical situation leading up to the elaboration of a project? What phases are most recurrent in the project elaboration process?

There are different stages in the coming together of a project. I need some time in between those moments for ideas to settle down. First, there is a clear starting point, the beginning of a research, a question or condition/s that set the tone for the work to come. Then the body gets more involved; there is a site visit, an interview, a residency or trip that helps me to think in a more embodied way. The actual making or production of something is when various elements come together, as well as the collaboration with others. This is the most important aspect I would say; because it is very important to trust the process. Not to make decisions too soon or rush to any conclusions. For me, the subtle moment between the making and the final realization is a very specific dynamic where trust, joy, but also serendipity and improvisation play a huge role. Lastly comes the execution or display of what you have made and the interactions with the public which that entails, along with you own reflections and thinking.

What do you hope communities will gain from experiencing your works?

A sense of collaboration, of enjoyment, and the idea that it is worth doing what we do. Also, the chance to be less judgmental and more kind to ourselves when we create things.

And what, instead, do you hope they will unlearn from you? Is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

The idea that something is new. I feel that everything we do is a recollection, a transformation of previous thinking and making.

Who are the thinkers who inspire your work?

Poets such as Circe Maia, Idea Vilariño, Juan L. Ortiz, Laura Wittner, Mariano Blatt. Mainly literature, fiction and poetry.

In what way does your practice help us imagine new worlds or a more habitable world?

I thinks thanks to the use of fiction (which I borrow from literature and poetry), storytelling, humor as well as the use of history and what I call “irreverent” research (artistic research, less formal, less in response to a particular science). All those help us to recreate, to retell our lives and how we live.

Note biografiche

Visual artist and performer from Buenos Aires, Mercedes Azpilicueta (La Plata, 1981) lives and works in Amsterdam. She habitually collaborates with archives, libraries, historians, dancers, textile designers, and urban planners to bring to life her layered installations, in which tapestries, free-standing sculptures, videos, objects and salvaged materials are combined with architectural elements. Azpilicueta’s works traverse history and geography to give voice to unheard and dissident figures from the past, stories, myths, and legends through which to explore the affective qualities and political dimension of language and voice, the processes underlying the formation of cultural memory and the construction of gender and subjectivity. Her work is manifested in performative and sculptural installations, inspired by speculative and fictional Latino literature, Neo-Baroque art history, contemporary popular culture, and new materialism theory. Through collaborative and interdisciplinary practices, she combines “precarious,” craft-based techniques—historically associated with domestic obsolete knowledge—with industrialized productions.