Breath is the visible sign of our relationship with the mountains, the tangible trace of the encounter between the body and altitude. A mountain landscape can leave us breathless or take our breath away, but fatigue can cause us to lose our breath and force us to catch it again. When it’s cold, we can see our breath running along its own path after a simple exhalation, on while uttering a word or a song, for breathing is also and above all the essential engine that modulates the voice and allows it to be emitted.

In 1977, ethnomusicologist Roberto Leydi edited the publication of Bergamo e il suo territorio. Mondo popolare in Lombardia (“Bergamo and its territory. Popular Culture in Lombardy”), a volume accompanied by a vinyl record, the result of field studies and recordings, collecting traditional folk songs from the farming, textile, and mining communities. With regard to the songs sung by the Dossena Miners’ Choir featured in the collection, Leydi speaks of “a strained and voiceless emission that seems typical of mining areas” and adds: “the way of singing (which in other respects is typical of the Alpine area) is likely determined by the fact that all or almost all of the singers show more or less pronounced symptoms of silicosis.”

A shortness of breath directly impacts the form of singing. History and the environment layered into the mucous membranes. This is the starting point I took, following in Leydi’s footsteps to listen to the songs of Dossena, with the intention of focusing on the pauses and their incredible density.

In Leydi’s writings, the singers of Dossena are presented as a “choir”: so in my mind I form the image of a formal group of singers who meet regularly to rehearse, all dressed up in a particular uniform, but when I meet Luigino and Ermanno for the first time, they tell me that “there’s no choir, here everything was singing, we sang all the time, after work, in the taverns, always.” Luigino Alcaini and Ermanno Micheli are the sons of miners from Dossena. Luigino worked in a nearby gypsum mine and Ermanno performed various tasks outside the Dossena mine. Both sing and keep the mining songs alive in the village’s social events and in the festival dedicated to Saint Barbara, the patron saint of miners.

I met them for the first time thanks to Walter Balicco, one of the key figures responsible for reopening the Dossena Mines to the public, the councilor for tourism and a singer himself. After some initial chatter with them, we organize a second meeting inside the mine, together with Filippo Alcaini, Rocco Bianzina, and Gaspare Alcaini. It is a very emotional moment. With great enthusiasm and at the top of their voices, Luigino, Filippo, Rocco, Gaspare, Ermanno, and Walter sing in front of me amid the drops of water falling onto the damp rock.

The two songs that most touch me are Anche ‘l mio padre and Fin da bimbo, ones that in different ways tell the story of young adults who, in order to earn a crust, start working in the mines despite knowing the risks—ones already run by their fathers—and end up badly affected by the time they reach their early twenties.

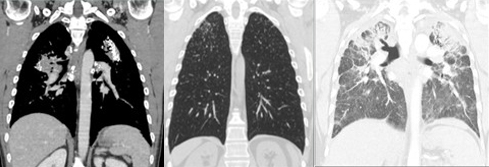

Sadly, both songs highlight that there are no doctors or medicines that can cure their ailments, for silicosis is an irreversible disease caused by silica dust and other minerals which, once inhaled, settle in the pulmonary alveoli, causing a chronic inflammatory reaction.

Over time, healthy tissue is replaced by fibrous scarring: the lungs become stiff, lose elasticity, and the surface area available for the exchange of oxygen is reduced. This is why respiratory capacity progressively decreases, leaving miners short of breath even during the simplest of tasks.

Although silicosis does not cause dysphonia directly, the ensuing respiratory disorders can affect the voice: chronic coughing irritates the throat and vocal cords, while breathing difficulties hinder breath control, causing hoarseness and a lower tone.

Many details in my interviewees’ stories struck me: for example, children would also participate in mining life, hired to count the explosions of detonated or unexploded fuses—an activity useful for calculating the risks for the next day’s work.

Another shocking story is the death of Ermanno’s father-in-law during an explosion in 1969. In the year of Woodstock and the moon landing, there were still those who died down the mines in the province of Bergamo.

Rocco remembers fathers and uncles in the tavern crying as they sang, unable to hold the notes. For this reason, they had to lengthen the pauses, making the hissing and wheezing audible, and then come up for air to start another verse. Rocco also cries as he tells me this story.

Gaspare’s testimony highlights Leydi’s description better than anyone else’s. His father died of silicosis, spending the last years of his life with greatly reduced lung capacity, needing an oxygen mask and in a great deal of pain. Gaspare dedicated a poem in dialect to this condition, recounting the course of his father’s illness, a “great invalid of the workplace.”

Listening to these words and songs, I imagine the impact of mining life on the many generations that have gravitated around it and on those of today.

These men with their broken voices seem to me to be a population unto themselves, speaking their own language, or rather a different species whose vocal apparatus functions differently, and I wonder how much this may have impacted or still impacts young people in the area, given that the way we speak is always the result of the voices we have heard and carry within us.

But how much did silicosis really impact the Bergamo area, or Dossena in particular, in terms of numbers?

It’s not easy to say, explain Luca Rinaldi and Eris Ferra, doctors at Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital in Bergamo, whom I consulted in order to better understand the physiological course of the disease, since many cases went entirely unreported.

What emerges from the stories is a collective phenomenon, far-reaching, capable of—quite literally—silencing the voices of so many of the workers throughout the Bergamo area.

Yet Ermanno, Luigino, Rocco, Filippo, Gaspare, and Walter—from a decidedly later generation—choose to continue singing the songs of a time that seems so remote to most. Thanks to the work of its inhabitants, today the Dossena Mines are a place that is pleasing to the eye, where the colors of the surrounding flora and rock are coupled with those of the artistic experiences running through it.

Ermanno, Luigino, Rocco, Filippo, Gaspare, and Walter continue to sing, remembering the value of those pauses and treasuring them as a fundamental musical and historical element of the songs themselves.

Bibliography

Roberto Leydi (ed.), Bergamo e il suo territorio. Mondo popolare in Lombardia, Torino, Einaudi, 1984.

Video Recording

Silvano Richini

Audio Recording

Ruggero Bosso