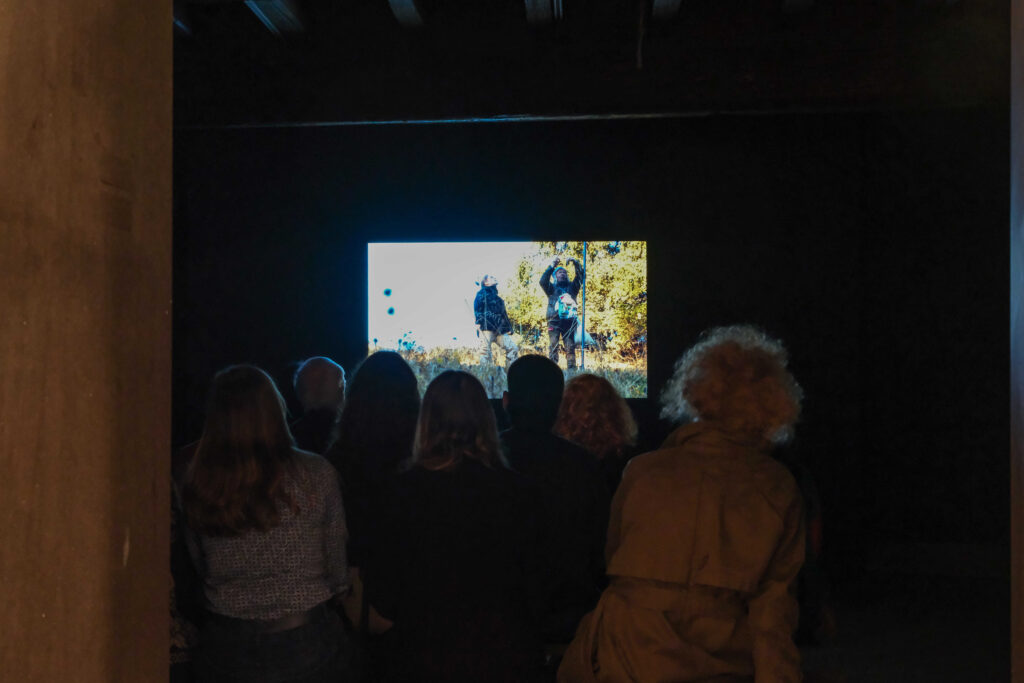

The first meeting of the series in the museum’s entrance hall—of which we publish an excerpt—featured Agnese Galiotto, artist and director of Migratori, in conversation with Francesca Rossi, ornithologist and technical-scientific assistant at Trento’s Muse, discussing the themes explored in the film, produced by GAMeC for Thinking Like a Mountain.

VALENTINA GERVASONI

For this first appointment, we join Francesca Rossi, ornithologist and scientific technical assistant at the Trento Science Museum, and Agnese Galiotto, artist and director of the film Migratori, produced by GAMeC as part of the Thinking Like a Mountain program, around the table in the museum entrance hall.

Galiotto’s work couples the ancient technique of fresco painting with moving images. She combines them insofar as one tends to include the other in some way. Her fresco paintings often respond to the need to experience a condition of physical proximity, of closeness to the observer. They have an enveloping nature; they give new meaning to places, sometimes unconventional and disused ones, thanks to the architectural study behind them, to their full, immersive development and the porous materiality of their details.

Migratori (“Migrators”) also offers this opportunity, and it is precisely by interpreting the alternation of its various types of shots that it emerges how—even with a language very different from that of painting—the artist’s desire seems to be to place us within a space and within the dynamics of observing it. The forest thicket fills the frame; hands and plumage in the foreground evoke details of certain medieval frescoes, while wide views offer glimpses of the sky.

I would like to start this conversation by quoting a book: What Would the Animals Say If We Asked the Right Questions?, published by the University of Minnesota Press.

The author, the philosopher Vinciane Despret, collected twenty-six “scientific fables,” as Bruno Latour defines them in the preface, which explore the interdisciplinary field of animal studies, challenging conventional stances on anthropomorphism and human-animal relationships. The book highlights an interesting paradox, namely how scientific knowledge of animals is created in artificial, laboratory conditions, in fictitious settings, and in response to decidedly human motivations.

However, Despret draws our attention to the term “anecdote” and how it is used to dismiss the experiences of those who spend their whole lives with animals, yet who may not be part of the scientific community. These may include farmers, breeders, trainers, pet owners, etc. The author argues that these people know aspects of animal life unlike those to be found in the laboratory, and that they could prove useful to science if only they were allowed to be part of the debate. Anecdotes are therefore those interactions that occur spontaneously with animals—including the daily practices of handling animals in a scientific context. Migratori, as we have seen and will explore further, contains many such anecdotes. But what are the right questions, to go back to the provocative book title?

Asking the right questions requires the imaginative task of wondering what animals ask themselves; it requires curiosity for the situations that interpret our relationships with them in order to develop a mutual truth, without assuming equivalence and/or certain knowledge of the motivations of our fellow species.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

I started thinking about this film when I was living and studying in Germany. I would return to Italy on the night buses that cross the whole of Europe. Those who have made these journeys, especially those that cross national borders, know they can be quite tough. Quite a few times, for example, I had to get off the bus with other people for a document check in the middle of the highway. While I always got back on the bus, on some occasions there were those who had to interrupt their journey at the border because they weren’t carrying the right documents. These were major trips for me. They certainly made me feel privileged but also vulnerable.

When I discovered that there is a scientific research project studying bird migration which takes place on the same Alpine passes that I crossed, I thought investigating it could be a way to channel these feelings. I looked for information about the project [ed.: the Progetto ALPI] and called Francesca Rossi who, even though she didn’t know me, invited me to come and see their work for myself.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

All the birds shown in the film, those tiny living creatures—some weighing as little as five grams like the goldcrest—also cross the Alps, traveling thousands of kilometers from central and northern Europe to spend the winter in the Mediterranean basin or even further south. When the birds arrive after their post-breeding migration, i.e. when they have finished breeding in central and northern Europe and start moving on, the first obstacle they encounter is the Alpine Mountain chain. The Alps represent a dramatic moment because in the mountains the weather can change rapidly and temperatures drop. There’s no certainty of finding food or shelter. Undaunted, these birds set off every year, traveling over the mountains right where we cross them to, i.e. through the passes. We go there to study them because it’s the only point where it’s possible to intercept them in some way, both visually and with these instruments that are nets, called “mist-nets,” through a method of investigation called scientific ringing.

It’s not easy to study animals that live up in the air most of the time. Until a few years ago, along those passes there were only double-barreled shotguns and other methods of capture that are now illegal. Because it’s in the passes crossed by the migration paths that the birds descend almost to the ground and where we can intercept them. In fact, today on those same passes there are ringing stations that try to intercept them to study and protect them. We also deal with promotional and educational activities for children and adults. Because showing the animals in our hands means getting to know them and therefore caring about protecting them.

Migratori passes through two locations: one along the Serio River Park, the Capannelle station, in Zanica. The other, the Brocon Pass, in Trentino, at 1,750 meters above sea level, is one of the highest passes where we study migration throughout the Alps. The birds also fly over passes at higher altitudes but clearly they choose the easiest routes if they can, but sooner or later the Alps are inevitable.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

While I was working on the film, I realized that we often hear many songs, many bird calls, which to the uninitiated all sound the same; instead, working on the audio—and spending time with you—we tried to understand exactly which animals live in that environment, how they sing to each other, how they talk to each other when they sing. Their song is communication, a language we are unable to interpret. The audio was therefore not constructed by inserting birdcalls to fill the sound space, but adapted by thinking of the sound as a territory, with its own specific characteristics. The musical part, composed by Nicola Cocco together with Luca Venturini, worked on a sound that might evoke the wind. Precisely in relation to the endearing image of the Brocon Pass, we thought the most suitable musical instrument would be a wind instrument, a clarinet, something whose sound crosses space, passing through the meshes of the nets and which, as I see it, ideally interprets the migratory movement and indeed the environment.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

Birds emit many types of vocalizations, but for us they just “sing.” They have more composite, musical vocalizations, which tends to be longer, that characterize the species and which begin at the reproductive phase. This song usually has a very specific purpose. In the Palearctic, it is usually the males that sing; in tropical regions the females also sing. When the male sings it means “this is my home, this is my territory”; he makes himself heard by the females, he tries to attract them; the best singers attract more females and therefore have more chance of reproducing. The production of songs and calls is hereditary but for many songbirds learning is also important. Songbirds learn to sing exactly as we learn to speak; they have a period—akin to the babbling of human infants—in which the baby bird repeats what it hears from its mother; and like the fetus, from inside the egg the chick begins to listen to the sounds of the female that is brooding it. When it is born, the chick already makes sounds very similar to those of its parents, and from that moment on it begins to learn the song of its species.

Clearly, the genetic component is fundamental: if a nest of great tits is found near that of a family of blackbirds, the young great tit will not learn the blackbird’s song, and therefore they will not become “bilingual” or “trilingual.” In their DNA, they have the structure of the song of their own species, i.e. an innate scheme for developing species-specific song, but they must listen to and memorize the songs produced by adults and then reproduce them correctly at the start of the breeding season. The young bird will begin its first reproductive season by performing its first song. It won’t be as good as that of the adults, but it will continue to improve and in the meantime it will have already crystallized its song. Another wonderful predisposition of songbirds is the ability to reproduce the sounds they hear. Twenty per cent of songbirds imitate sounds and noises, and this serves to enrich their own song, making it more complex and more attractive to females. I’m not referring to lyrebirds or parrots, but to small songbirds, such as the greenish reed warbler, which are unexpectedly excellent imitators.

And then there are all the vocalizations heard in Migratori, because Agnese Galiotto’s film was made in the summer-autumn period, when most birds have finished breeding. Most of the sounds you have heard are not songs but calls, produced by all birds, of all ages and at any time of year, and which serve different functions. An example of this are the danger signals that are the same for many species: a prolonged hiss means something is coming and that one should move away; if a blackbird or blue tit hisses, then everyone (not just blackbirds or blue tits) hides, taking cover in the vegetation because they understand there’s a threat. Some species use these sounds to explain what kind of danger is lurking; for example, the mustached warbler, by hissing in a certain way, warns its young if a bird of prey is approaching from above, so that they all crouch in the nest, or if a snake is coming up from below, and so encourage them to escape from the nest. All this is contained in a single sound.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

I remember a passage in the video where you say “I don’t know what kind of bird it is”, and immediately the other colleague, Laura, replies “a foreign warbler” hypothesizing a species that makes similar noises to the one heard but one that has never been caught at Brocon and probably follows a different route than the one that goes over that pass.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

When I arrived in Trentino to work here—I’m from Tuscany—I was amazed to hear the song of the blackcaps! They sang so differently from the ones in Tuscany. In fact, birds also have their own dialects! Songbirds have a real musical instrument: the syrinx, the marvelous organ at the junction between the trachea and bronchi and which, thanks to a particular set of muscles, they are able to make vibrate as air passes through it. Some species can even produce two independent notes simultaneously, which is truly magical.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

Besides hearing, there’s also sight. When deciding how to set up the shoot with Elena Grasso [ed.: director of photography], we thought a lot about the how to get up closer to the animals. From a distance it’s not possible to capture certain colors: while handling the citril finch, you can capture all the shades of gray and yellow, for example. For me these are pictorial aspects, in this sense the moving image is just like painting.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

Colors are very important too; this element is also part of their language. Animals communicate with everything, just like us, after all. I also talk a lot with my hands. Our posture, the tone of our voice, our looks—they are all forms of communication and they all do the same thing. What’s more, they have the advantage of plumage with colors and patterns that can be used for camouflage or communication. For example, in many species, the different coloration distinguishes the males from the females and, in particular in the same species, the males with more intense coloring indicate having a better quality of life and therefore are more readily chosen by the females.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

To make Migratori I returned to the Brocon Pass a year after my first visit, and I also wanted to go to a different station, Capannelle, near Bergamo airport. The film shows how the planes fly by very close. And there, however, there are a lot of birds, maybe fewer because it’s not a mountain pass where they all passes through, but it’s a station where it’s possible to spot many different species. There’s the green woodpecker, which at one point landed right in front of the nets. This bird carefully dodged the net at the last minute. You need to have an encounter, an experience; you can’t have a memory of nature without having a direct experience of it; it’s something completely different.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

You were amazed to report that despite being a bird-ringing station near the airport, it is full of birds. The environment around us has always been full of birds; it’s us who have gone everywhere, it’s us who are so intrusive, unfortunately, and we have driven the birds away.

Many plane crashes are caused by aircraft colliding with flocks of birds. Bird strikes are one of the problems airports have to deal with. Airports are areas that birds like to frequent. In fact, how many open areas are left on the plains? Not many. In Trentino, most of the areas at the bottom of the valley are occupied by various types of concrete structures: roads, houses, factories, apple orchards or vineyards. Meadows are environments that many birds use to feed and rest, but there aren’t many left.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

Also with regards to what Valentina was saying at the beginning about the value of anecdotes, the way in which you ornithologists interact with animals, your knowledge of birds, in the awareness that you can’t fully interpret them, leads you to get very close to the animal, and to understand when it is “ worried,” when you have to let it go because maybe it’s cold, and this attention, in my opinion, is symptomatic of an understanding—perhaps not in scientific terms—of the other, one that wouldn’t exist otherwise.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

The Progetto Alpi began in 1997, coordinated by the Higher Institute for Environmental Protection and Research ISPRA, based in Bologna, together with the MUSE in Trento. It is a national project; there are fifteen stations that every year work like so many windows along the Alps that allow us to gain insight into bird migration. Since the project began, we have all started to work in a standardized way, with the same procedures, the same rules; we provide training by making a lot of direct experience available. This brings us back to the initial point: you learn to understand animals when you spend a lot of time together, it can’t just be an occasional thing. First of all, respect is needed: that animal is a living being, unlike me in many ways, so it must not be hurt, and only then comes what interests us, i.e. scientific research. For example: the first liberation recorded in the film is that of a wren, weighing eight grams. It is a “net picker,” meaning that it doesn’t fly into the net but waits just outside it, then it enters and starts pulling at the net here and there with its beak, getting one wing stuck in a hole and then a foot in the other. When you go to remove it, the wren is a ball, all one with the net. Freeing it requires patience; for those who have never seen how it is done, it can be shocking, you may think that stress is caused to the animal, but the handling and release are done according to techniques that, if followed carefully, lead to their release without any harm.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

The way you speak in the film—and the fact that you also talk to the animals even when you’re not being filmed—means the animals empathize with you and it brings into the recording, and thus the documentary, a lot of the sensitivity that you and your workgroup have towards the animals.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

Animals are very sensitive to our agitation, our calmness and our way of speaking. Even in the home with the cat, the dog or the canary in a cage: animals immediately realize when something is wrong if you shout, and there are sounds, rapid movements that are immediately perceived as danger signals. Perhaps we do in fact have a way of communicating with other species.

If you think about it, it’s also a way we ought to adopt among ourselves. Like even when we speak different languages, we can always understand who has a respectful way of approaching the other and is able to express their primary needs.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

This element was very helpful in the making of the film because I believe it can help someone who has never seen the practice of bird ringing to understand what is happening, what that bird is, how it behaves, and how the work is done.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

We need to be curious about what’s around us and we’re not curious enough. We don’t listen enough to our surroundings. I’m talking about birds, but the same goes for any other animal.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

This goes for animals but also for the landscape, for the way we look at space, the way we think about nature in general.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

You filmed from the forest, from the bottom up, and personally I could watch it forever. Yet I’ve seen that station every year since 1998, for a month, a month and a half. In short, I know that forest pretty well. And I had never seen that sunset you captured before now. I certainly haven’t seen anything like that. Observation really is a skill that needs to be practiced.

Q&A

How long do the migratory stages last?

FRANCESCA ROSSI

This is the most difficult question you could ask, because migration is a very long process. Post-reproductive migration, the autumn migration to be precise, for some species begins as early as the end of July. This means, for example, that by the end of July, the willow warbler has already reproduced in northern Europe and is now on its way back south. Just think how fast they are. All those species that have to go south of the Sahara Desert, which obviously have a longer journey, have to leave earlier, such as the swallows or the pied flycatcher that you saw in Migratori at the Capannelle station. The ones you saw at the Brocon Pass station, on the other hand, stop off earlier. These are intra-Palearctic birds, which means they stay in the area that includes all of Europe right up to North Africa. They don’t cross the Sahara Desert and because of this they can leave more calmly. With impending climate change, these phases are changing further. Birds, unlike humans, are not heedless of the problem—they are already adapting.

Overwintering, i.e. the period between one reproduction and the next, needs to be spent in a place where there is a food supply. But what about a chaffinch that used to leave Sweden (for example) when the cold weather came so as to spend the winter in milder Spain? Assuming that Sweden becomes a milder country in winter with the presence of insects, why would it want to leave? And so certain species of birds are delaying their departure for longer and longer periods of time. When we capture them—in the film you saw the procedure—we put a small ring with an alphanumeric code and the initials of our ringing center around their leg; we take morphometric measurements, we look at the development of their muscles and their fat deposits, and when possible we determine their age and sex. All this data is sent to the ringing centers in the various countries that are in communication with each other. In this way, the little ring that we attach will be used to determine the origin of that animal in the case of its recapture.

There are also some populations of the same species that are migratory and others that are not. This is the case, for example, of the blackbird. Blackbirds that reproduce in northern Europe are migratory ones. Blackbirds that live in our cities, and therefore have optimal conditions all year round, tend not to migrate and this makes us realize how malleable their behavior really is.

Q&A

Over about twenty or thirty years, the species of birds to be found outside my house have changed considerably. The ugly birds—the pigeons and magpies—have driven off all the beautiful ones.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

They’re all beautiful! The birds you called “ugly” are simply general birds, the ones that have been best able to adapt to us. The “beautiful” ones are perhaps those birds that need a more complex environment—like the blackcap or the nightingale. We have replaced complex environments with our gardens, with orchards and monocultures. We no longer have shrubbery, marshlands or uncultivated areas. We have modified the habitat and this modification has influenced the presence of the species. Years ago, I went to Paris and saw a woodpigeon in the city. I was surprised because in Italy you don’t see wood pigeons in cities. It’s a migratory bird, as I knew because hunters used to go and shoot them on the Apennine passes. For me it is a beautiful bird and it has a powerful and fast flight. It is not a pigeon even though it has similar colors. It is an animal that cannot be defined as “ugly.” Now, however, it has become “ugly”: why? Because it’s everywhere, even in Italy, but it’s not the presence of the woodpigeon that makes other species flee; it’s the alterations that we have brought about in the environment.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

Another aspect of the film is caught up in the debate about birds being ugly or beautiful. The initial idea was to work on a type of animal with which we don’t easily identify: we know little about birds in general; we rarely identify them without thinking about them, justifying this ignorance with their supposed widespread similarities. Seeing them up close, and even having the chance to film them up close, allows us to appreciate their beauty. That’s what happened to me with the nutcracker, that bird that appears in the fog: it has white dots and is otherwise completely black. From a distance I thought it was a very ugly bird, even a bit mean; but up close I could see the dot patterns and its intelligent gaze.

SARA FUMAGALLI

It looks like Agnese tried to be democratic towards you too; there is certainly a will to restore a sense of diversity in the world of birds, and so to identify the various species and restore their characteristics, behaviors, and vocalizations, but it seems to us that she did the same thing with you as well. The fact that she focused on some of you ornithologists shows that in your being scientists and professionals at the same time, you establish different relationships with these animals through your work, also based on your inclinations and personalities. I really liked how Agnese brought out this aspect in the film, trying to capture the nuances of behavior, always demonstrating that at the base there is that respect we were talking about and an awareness of their vulnerability. Your desire and ability to handle them reflected something that goes beyond being simply scientists, but people.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

We asked them all who their guiding bird was. It’s incredible how each one said a species and that species not only resembled them aesthetically but also in character! Francesca said the robin. Laura said the jay, and I thought it really had the same eyes as her.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

In these stations there are some who really have difficulty being in front of a camera. Agnese realized this immediately. She respected this even though she might have liked to film these subjects.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

I also had this scruple when filming the animals, so much so that we decided to use lenses that afforded us a degree of closeness and detail on the birds while still being physically distant. Until now, I have always filmed precisely considering the size of the camera. The common term for filming is shooting. Indeed, when you film, you have a weapon, you are in a position of power that is a bit complicated to manage. This is one of the reasons why I came back to film several times over. It seemed to me that the camera became less powerful in some ways, and that they too would feel less threatened by that cumbersome object, by the people filming, by the need to understand how to set up the framing because we can’t talk while they are working. Empathizing with others also means trying to understand how to represent them without being imposing.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

The camera objective is undoubtedly akin to a weapon, as you said: many birds seem to recognize when something is pointed at them, and therefore go into a stress phase. In fact, Agnese and the crew always stayed as far away as possible from the animals so they were very calm.

AGNESE GALIOTTO

An interesting aspect regarding the identification and work of the ornithologists who follow this project is that there is a lot of downtime in which they are simply listening and observing. So we also worked on observing the space, waiting for a bird to pass right through the frame. Sometimes it’s exhausting, but it’s a lesson in itself, knowing how to observe. It teaches you to understand that the animal’s timing is not the same as ours; sometimes you think too much time has gone by, so you turn off the camera and just at that moment, there it comes.

FRANCESCA ROSSI

In the film, there is a fir tree with two finches: in the first part the male leaves and calls the female to tell her it’s time to go, using the sounds I mentioned before. He jumps down from the branch, she adjusts her plumage and follows him. This meaningful detail that you managed to grasp shows one aspect of migration. Migration is something they decide to do. The finches migrate in formation, in large groups, they wait. If one is alone, it calls out until other specimens arrive, and thus the flock is formed.

SARA FUMAGALLI

This conversation made me think of something that anthropologists often say, namely that anthropology is frontier knowledge. It is possible to get close to someone who is human like me, with a culture very different from mine, but it is precisely the awareness of remaining anchored to who I am, to what my knowledge is and that of the group to which I belong, that allows me to stand on that boundary which lets me get in touch and push myself towards knowing the other person that I will never be able to fully get to know. However, it is in this very gap that the encounter takes place, that the dialogue can begin or the “right questions” that Valentina was talking about at the beginning can be asked.

VALENTINA GERVASONI

I would like to conclude this meeting with the key question of our program Thinking Like a Mountain. What is a community for you, how can a community be built and what is its value?

FRANCESCA ROSSI

For me, that’s a very simple question to answer. The community is that group of people that you saw clearly in the film; it’s that group of people with that group of animals. Being able to form groups of people who, together, do something they believe in and spread the word about it. In our job, we work very hard but we do it together. A community is necessarily made up of many different elements that must remain so.

VALENTINA GERVASONI

Going back to the question I asked at the beginning, in fact Despret’s book is above all a critique of anthropomorphism and also of the identification between species. Agnese, what do you think?

AGNESE GALIOTTO

I think my whole work investigates the sense of community. In film and painting, it is as if I were tracing an autobiography based on those closest to me. For the past year, I have been living in a mountain area, although I am not originally from this town but from one not far away. To enter a community, you have to accept that you are the different one: entering a space that is established, fitting in without treading on toes: that’s how you can nurture it and make it thrive.